But I was having a good time, having shaken off the shackles of having to seek permission for virtually every move I made. I’d stopped—for the most part—sneaking out to smoke and taken to staying out well past the midnight curfew that had accompanied me through my previous dating years, swearing without fear, and developing ideas of my own that seldom coincided with those of my family.

Something that happened well before that time, though, was my interest in politics, one that had its foundation in the presidential election in 1960. Our fifth-grade class discussed it on a daily basis, debating the pros and cons of Kennedy and Nixon with raised voices and very little actual knowledge. The election board lent us a desk top prototype of a voting booth, and we held our own election. The results were predictable, although not nearly as much then as they are now.

We saw things through those years. Even where I went to school, the student body was silenced and horrified by JFK’s assassination. Not so much when it was Dr. King. We were not diverse there in the cornfields, people around us still used the n-word frequently, and being different in any way wasn’t something to be encouraged; while I had met black people, I didn’t actually know any. None. While I was sorry for Dr. King’s death, I couldn’t begin to understand the grief, anger, and hopelessness everyone in his race must have felt. I bought into “different” because I didn’t know any better, but I should have. I should have.

It didn’t occur to me until June of that year that I should have dug deeper to understand. When Bobby Kennedy died, it was my first up-close acquaintance with social hopelessness, my first bout with sharp, sustained grief that didn’t have to do with someone I personally knew and loved, my first anger at people who think hate is okay. More than okay, it’s to be revered, shared, and cultivated.

I should have dug deeper.

But I didn’t mean for this to be a soliloquy on politics or how I feel about hate. Except maybe I did. I remember that day in June when Bobby was shot. My mom woke me to tell me, and even though he was still alive, we knew it wouldn’t be for long. The madman with the gun was very thorough in his destruction of the person many of us thought would be our country’s savior.

|

| History Nebraska |

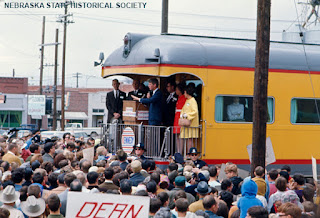

I’d seen him that April on his whistle-stop tour. I skipped school to go to the depot in Peru and listen to him talk from the rear platform of a train car. Oddly enough, I can’t remember if it was a caboose or not, which sounds like a non sequitur but has been fidgeting around in the back of my mind all the while I’ve been writing this.

I was short and the area was packed. Although I could hear, I couldn’t see until the man behind me, easily a foot taller, put his hands under my elbows and steered me straight through the crowd to where I stood right at the end of the train. Right there! I could see Ethel Kennedy’s makeup that drew commentary from my Republican friends and their children looking bored and Mr. Kennedy speaking earnestly.

I thanked the man behind me, bursting into laughter when I saw that the front of his shirt was plastered with badges supporting Eugene McCarthy for the presidential nomination.

“Things will be better,” I said. “When Bobby’s elected, things will be better.” I was buoyant with hope, with faith in someone who was up for rattling the cages of tradition and conformity that had kept me so unaware.

We’d get us out of Vietnam.

We’d end the hate.

We’d see to it that there was No More War. As a matter of fact, violence would disappear altogether.

No one would ever be hungry.

Everyone would have not only freedom of religion but freedom from it, too, if that was what they wanted.

We’d save the planet.

Racism would disappear. (That was an afterthought with me—I still didn’t get it.)

But then Bobby died.

My life changed irrevocably that year I turned 18. Because Bobby Kennedy lived and because he died. Our generation didn’t do any of the things we thought we would, but I learned to widen the scope as much as a white girl from the cornfields could manage. I learned to keep trying. Keep trying. Keep trying. And never, ever give up.

And at the end of the political day, I’m still looking for Bobby.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)